Organizations that contributed to this investigation: Demagog Poland, Facta, Maldita, Newtral, Les Surligneurs, Pagella Politica, The Journal and AI Forensics

A toddler with big blue eyes is looking happy among Christmas lights. A young and beautiful woman walks home alone in the night, feeling safe. «Do you remember how beautiful Germany once was?», asks Alice Weidel, leader of the far-right German party AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) on her X profile, referring to these scenes, shown in a video. So beautiful and yet unreal, because in fact these images are AI-generated.

Throughout the German electoral campaign in early 2025, the AfD has persistently used AI-generated visuals to convey the message that Germany is in danger because of migrants. These are often portrayed as dark-skinned threatening men, drawing a stark contrast with the innocent blond child among Christmas lights (a clear reference to the then-most recent Christmas market attack of Magdeburg in December 2024).

Such content, however, is not a German peculiarity; throughout Europe, indeed, far-right parties are increasingly relying on generative AI to spread their political messages.

Electorate engagement

In July 2023, Polish right-wing politician Dariusz Matecki (Sovereign Poland) posted a video predicting disaster if centrist Donald Tusk (Civic Platform) came to power with the parliamentary elections scheduled for October 15th, 2023 (which eventually happened).

The disasters shown in Matecki’s video, presented with AI-generated images, involved illegal immigrants breaking into Poland and classes in schools taught by transgender people with very exaggerated features. Nativist-protectionist or anti-immigrants content as such is easily represented by AI, which is «quick in offering visually compelling images that resonate with far-right messages», says Claes de Vreese, Professor of AI and Society at the University of Amsterdam.

In 2024, a similar strategy was adopted in France by far-right politician Éric Zemmour (Reconquest), who posted a video of AI-generated images showing the alleged consequences of Emmanuel Macron’s presidency: “mass immigration”, woke ideology, and lack of safety on the streets. During the European parliamentary and legislative elections of 2024, many other French far-right parties relied on AI for their political campaign. A report published the same year by the non-profit organization AI Forensics has shown that AI-generated visuals were used to amplify anti-EU and anti-immigrant messages, as was the case for the political campaign L’Europe sans eux (“Europe without them”), promoted by the far-right party National Rally. Specifically, Head of Research at AI Forensics Salvatore Romano underlined that in the context of elections «social media platforms are underestimating a systemic risk» which could compromise the impartiality of the electoral process, and that stricter content moderation is needed.

Nonetheless, this political communication strategy later took off in other countries as a way of boosting engagement and mobilizing the electorate. As previously mentioned, the AfD in Germany widely generated AI content during the last electoral campaign, with images depicting on the one side the “ideal Germany” of blond blue-eyed people and on the other side the dark-skinned migrants allegedly profiting off from the state. In September 2024, just before the elections in Thuringia (Germany), the local AfD candidate Stephanie Hüther-Keseling shared an AI-generated video on Facebook pushing for “remigration”, a far-right racist plan to deport asylum seekers, immigrants and even citizens with passports that are considered “non-assimilated”. Similarly, in Ireland, the newly founded far-right party The Irish People adopted the same rhetoric, using AI representation of local people to draw a contrast between the “pure” Ireland of the past and its catastrophic present.

Pop culture and xenophobia

The narrative is simple: the “good old Europe” is lost because of immigration and “our” culture is in danger. The solution? Voting far-right parties that will restore Europe as it once was. «We live in an era of disaffection from politics», though, and in order to reach the electorate «the far-right leverages pop content spread through social media channels», says Daniele Battista, Research Fellow in Sociology of Cultural and Communicative Processes at the University of Salerno.

In April 2025, Italian far-right politician Silvia Sardone (League) shared an AI-generated video showing “Milan in 2050”: crowded streets, dirt everywhere, monuments covered with Islamic flags, squares converted to chaotic souks, and churches turned into mosques. «Do we really want this future for Milan and the European capitals?», she asks in the caption.

Inventive? Not really. Sardone, as she explains in the caption, was «reposting a video circulating on the internet». Specifically, she was following a TikTok trend of videos imagining European capitals in a set period of time; a trend which later took a racist spin, fueling conspiracies theories such as the one of the “great replacement”, with which «far-right ideology is deeply intertwined», says Fraser Crichton, software developer at AI Forensics.

Similarly, in March 2025, the Spanish far-right party Vox joined the “ghiblification” trend of political propaganda, and relied on the “barbie doll trend” to attack the alignment between People’s Party (center-right) and Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (center-left) in the European Parliament. In Ireland, MMA fighter and far-right influencer Conor McGregor has shared the action figure AI meme of himself as president of Ireland (no longer available on X), with a pack containing references to “deportation orders” (i.e. remigration).

Such affection to social media trends is the key strategy of far-right political communication, which fuels on memes: «This game plays out in the gray area», says Battista «since memes present themselves as harmless or ironic despite having an implied (radical) message».

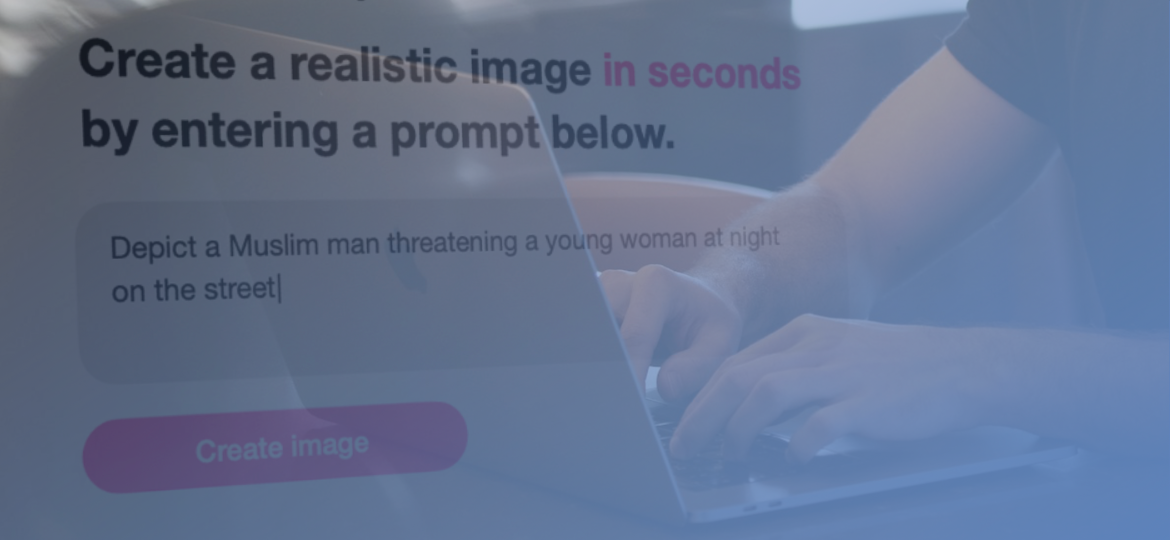

Ethical issues and impact

Through AI-generated content, the far-right is then able to convey an effective and emotionally powerful message, engaging and profoundly ideological. In the past months, for example, the League party in Italy created AI images of migrant or muslim people involved in recent news stories. In addition to headlines such as “‘Islam says so’: Iranian abuses wife and beats son”, the posts were accompanied by an AI-generated picture of the people involved, whose faces – that do not exist in reality – were often pixelated as if to protect their privacy, thus making the artificial pictures look more credible. In April 2025, the case was brought to the attention of the Italian Communications Regulatory Authority (Agcom) by opposition parties, who claimed the images were deceiving and designed to spread hate.

«People that propagate these kinds of claims probably don’t even think about them as misinformation», says Jonathan Leader Maynard, Senior Lecturer in International Politics at King’s College London. Indeed, the League party in Italy replied to the oppositions’ complaint by saying that all their images are based on facts. Whether the images themselves are factual or not, supposedly, does not matter. This does not come as a surprise, given that «the political business model of the new radical right», specifies Maynard, «is not based on verification by experts and institutional authorities» and that «it rejects by all means traditional means of communication».

Analogous cases had already taken place in other countries: in March 2024, for example, Polish MP Joanna Lichocka from far-right party Law and Justice shared a picture allegedly depicting a farmers’ protest ongoing in Poland.

An expanding phenomenon

The trend of using AI in political communication visuals is expanding in Europe, and considering that it has pervaded the countries of the major linguistic groups, it will probably soon reach other states as well, given the elections coming up this year in many EU Member States. In Poland, for example, politicians from Law and Justice used an AI-generated image of beautiful, fair-looking women supporting the far-right candidate Karol Nawrocki in the upcoming presidential elections of May 18th 2025.

The problem, however, is not confined to institutional actors and politicians. In Spain, France and Ireland, the organizations of the EDMO fact-checking network have detected various examples of far-right influencers (either AI or anonymous) that spread misinformation or politically charged visuals for propaganda purposes. According to Battista from the University of Salerno, the power of these “satellite pages” cannot be overlooked.

One of the thorniest issue of this phenomenon is that most of these AI-generated images are not clearly (or, at all) flagged as such: according to AI Forensics, in the context of electoral campaigns, this contravenes the requirements established by the Digital Service Act Election Integrity Guidelines, enforced in Europe in 2024. In general, as their report reads, it «undermines the effort to prevent the spread of misinformation». In some cases, specifies Maynard from King’s College London, such use of AI «can be even considered as a subset of misinformation», especially when not flagged. And this manipulation of public opinion, which tends not to care whether a content is real or AI-generated as long as it aligns with their beliefs, can put democracies on a dangerous slippery slope.

Lucia Bertoldini, Journalist at Pagella Politica/Facta and EDMO