Cognitive biases in news-making and fact-checking: a mixed methods approach

Author:

Mariavittoria Masotina, Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Liverpool (Department of Communication and Media)

Key words: cognitive bias, disinformation, fact-checking, digital tool

The advent of the Networked Society has radically changed the way we access (mis)information: real-time updates on social networks have created a continuous stream of information, contents often go viral before being fact-checked regardless their accuracy. The news industry must keep pace with this rapid context, reducing publication times regardless the complexity of the (mis)information ecosystem. Fact-checking a piece of news presents similar challenges as it takes several decisions to be made opening doors for cognitive shortcuts: What (fake) news to prioritize? What sources are necessary and/or sufficient to verify information? Where to look for evidence? What to highlight in a fact-checking report?

The LATIF project brings the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) methodology from the intelligence domain to the fact-checking realm to counter and control for cognitive bias in the fact-checking process. This methodology involves systematically considering multiple hypotheses to avoid biases and errors in decision-making. By applying ACH, the project aims to develop a new generation of digital tools to empower and improve fact-checking organizations’ decision-making processes. It seeks to answer the following research questions:

- What does impartiality mean for fact-checking, and what role is played by cognitive biases?

- Which cognitive biases affect fact-checkers in the selection of news to fact-check and in the verification process?

- How can structured techniques be adapted to help debias fact-checking?

- How can a digital tool be developed to help fact-checkers minimize cognitive biases?

- How can we measure the impact of the debias fact-checking tool?

This post focuses on the second question by introducing our recent study, “Cognitive biases in news-making and fact-checking: a mixed methods approach.”

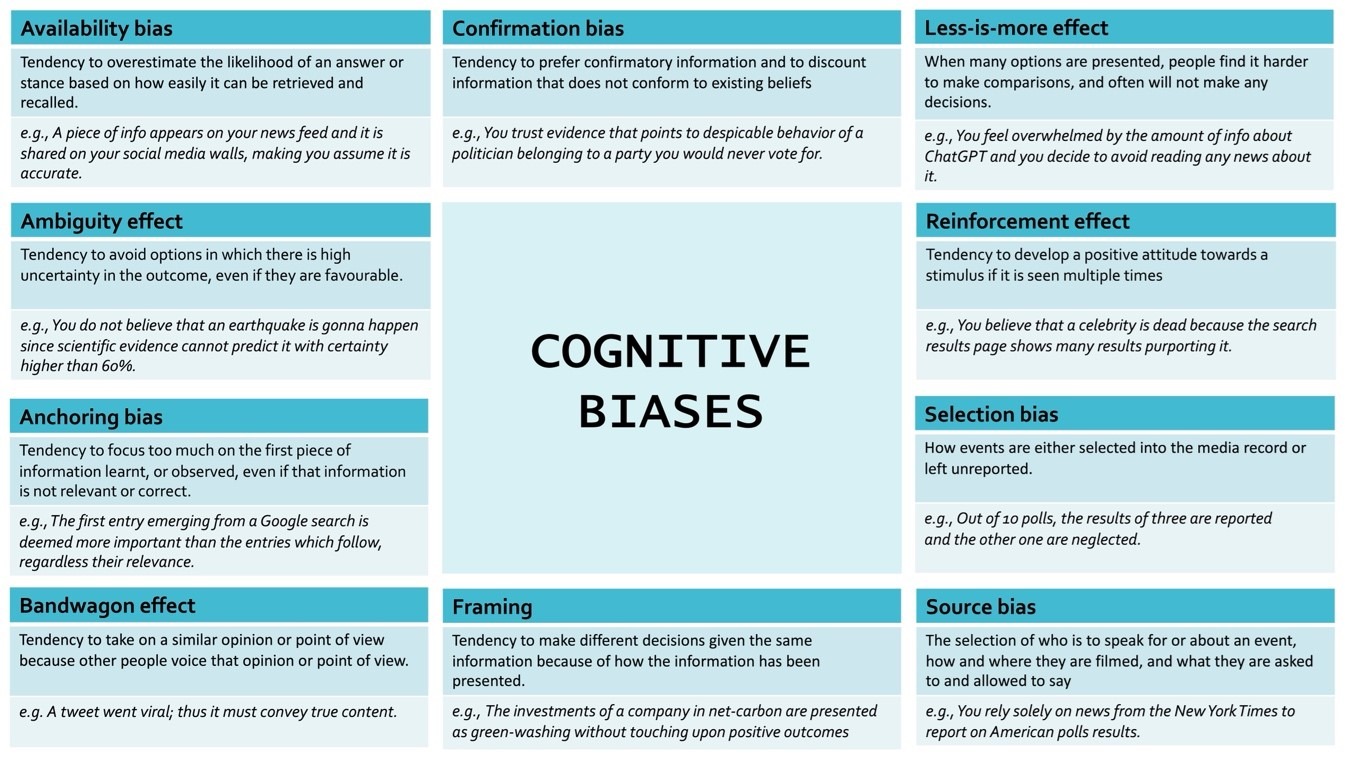

Cognitive biases are systematic patterns of thinking or decision-making errors that human beings tend to exhibit in various situations. They result from mental shortcuts and heuristics our brain employs to process information and make quick judgments, and can influence how we perceive information, interpret events, and make choices. In the context of misinformation studies, previous research has started to shed light on biases intervention in the audience consumption of news and fact-checks dissemination, but little attention has been paid to the news verification domain.

On these grounds our research offers the first empirically-based taxonomy of cognitive biases relevant for news verification, through two main steps (cognitive biases and fact-checking in theory and in practice).

First, we carried out a large-scale semi-automatic corpus analysis of scholarly articles retrieved through the Scopus Application Programming Interface, focusing on the theme of bias in the journalistic practice and news environment. We combined the emerging biases with those traditionally associated with Information Seeking and Retrieval (ISR), and selected those cognitive biases relevant for professional fact-checking. As a result, we ended up with a “cheat-sheet” composed by a list of 10 biases relevant for the online verification of information.

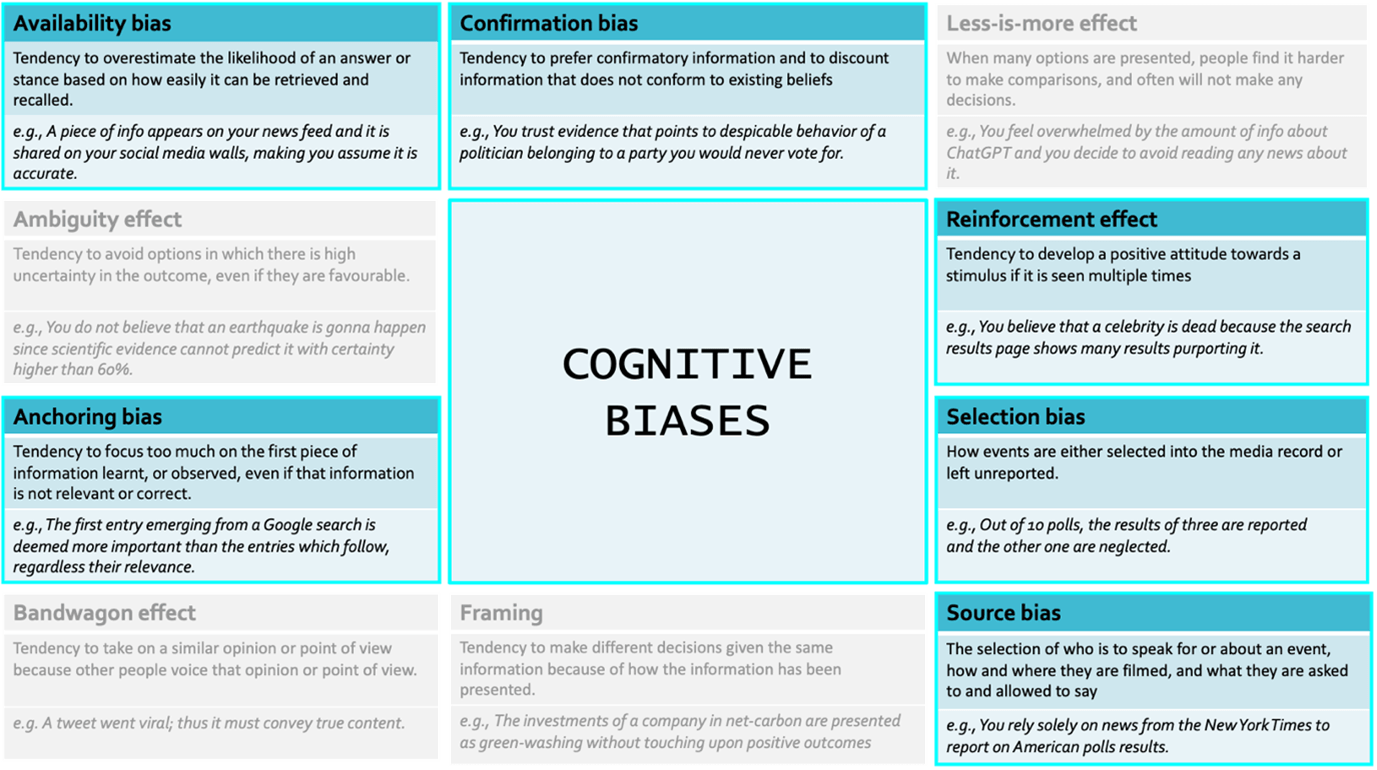

The second step bridged the gap between theory and practice. Twelve journalists and fact-checkers from different organizations and countries participated in a fact-checking simulation. During this simulation, they were required to vocalize their thoughts, reasoning, and impressions as they completed a series of tasks. Six out of the ten “theoretical” biases, namely anchoring, availability, confirmation, selection, source bias, and reinforcement effect were found as the most relevant. The same result was confirmed through a quantitative questionnaire, where we directly asked practitioners which biases most significantly impact the fact-checking process.

But the one-million-dollar questions are: Where do these biases come from? Are they all the same? How can we make people acknowledge them?

Relying on a linguistic and psychological theory of communication (Relevance Theory) we have understood that some of these biases (anchoring bias, availability bias, framing through images, less-is-more and reinforcement effect), are triggered by cognitive efforts, while others by cognitive effects (bandwagon effect, framing through text, confirmation, selection, source and ambiguity bias). The mechanisms of digital media affect our memory and prioritization processes… isn’t it easier to remember click baiting content that is everywhere online? The fact is that seeing a piece of information multiple times reactivates it in our working memory, reducing the amount of mental resources – attention and memory – needed to process it, and making it appear more relevant. Fact-checkers as humans must deal with similar struggles.

Now, imagine you strongly believe that a famous rockstar – let’s call them “Star” – is reckless and irresponsible. One day, you see a news article online with the headline: “Star Devastates Hotel Room in Wild Party!” Because this fits perfectly with your belief, you’re quick to accept it as true without much skepticism. However, if it is a fake news, your confirmation bias makes it harder for you to identify it as such. Since it aligns with what you already think, you’re less likely to question its accuracy. You will stop looking for other sources or evidence much sooner than you would if you believed the rockstar was cautious and responsible. Despite being non-partisan fact-checkers are (luckily) not stochastic parrots and hold beliefs, which inherently affect their world views.

We have classified the biases as related to cognitive effort (effort used to process information) vs. cognitive effects (update in worldviews). The two types trigger different levels of complexity to make practitioners aware of their intervention in the process.

Our study offers insights into two key areas: first, it aids in identifying cognitive biases that may influence the fact-checking process. Second, it highlights the effectiveness of explicitly articulating the background knowledge guiding decision-making, which can mitigate effort-related biases that may arise during news verification.

These findings are informing our co-design efforts with practitioners as we develop a tool to support them during the verification process.

Curious to learn more about the project? Feel free to explore further on our website!