Introduction

The European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) has its main focus on the European Union, but the Union does not exist in a vacuum. Many social and economic dynamics happening in the neighbouring regions, such as the Balkans or MENA, directly affect the EU. What happens in the field of disinformation is not an exception. A contemporary phenomenon of historical proportion, such as the migration of hundreds of thousands of people from the Global South, links Europe to the seemingly distant geographical area of Sub-Saharan Africa.

In order to have a better knowledge of the disinformation spread in this region, in September 2023 EDMO started cooperating with and dedicated resources to Africa Check, a fact-checking organisation with newsrooms in four African countries (South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya and Senegal) and a number of freelancers in different countries across the continent, to gather and analyse the disinformation about the war in Ukraine, and Russia in general, circulating in different African countries. In the investigation made possible by this effort, different relevant disinformation narratives – defined as clear messages emerging from a consistent content campaign (news, videos, images etc.), that are demonstrably false using the fact-checking methodology – have been highlighted.

The first one (“Russia has Africa’s support and vice versa”) is composed of false news that circulated mostly in Africa, even if some of them – sometimes because the languages used, like English and French, allow content to cross continental borders, sometimes even in other languages – reached also Europe. This narrative seems to be the one more specifically link ed to Moscow’s diplomatic efforts on the continent, and consistent with the Kremlin’s strategy of exploiting the West’s colonial past to present itself as the natural ally of African countries that suffered from European domination.

The other narratives identified in Africa are shared with Europe. The narrative identified by Africa Check as “Russia is a global power to contend with” largely overlaps with the narrative “Pro-Russia war propaganda”, e.g. exaggerating Russian military achievements, that was highlighted recently in the EDMO monthly fact-checking briefs. Similarly, the blatant denialism of the narrative “There is no war in Ukraine” has been a common phenomenon in Africa and in Europe (see the narrative “Questioning the war, from its reality to its motives” highlighted in the EDMO insights). Finally, the narrative described by Africa Check as “Ukraine as the bad (and good) guys” seems to overlap with two narratives identified by EDMO in Europe: “Pro-Ukraine war propaganda” and “Ukrainians and Ukrainian forces are largely pro-Nazi” (this one a sub-narrative of the broader one justifying Russian war of aggression). It is interesting to note the different prominence accorded to the link between Ukraine and “Nazism” in the disinformation spread in Europe (where it is extremely widespread) and Africa (much less so).

Disinformation narratives about the war in Ukraine: An analysis of claims circulating in Africa

An investigation by Africa Check

Almost as soon as Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, false claims about the war began circulating online in Africa.

While the continent and its people may seem far removed from events in Europe, Africa is an important stage on which global powers seek to erode the influence of their rivals and enhance their own stature. Attempts to advance strategic narratives and build influence via the media, traditional or social, therefore also include Africa.

The period immediately following the invasion was marked by a spike in disinformation on social media. In the months since then, the spread of false claims has slowed, perhaps overtaken by more recent events or simply driven to dark social media platforms where claims are often not subject to content moderation. Another challenge is that many claims shared in Africa about the war are not outright false, but may be presented in a misleading way and are hyper-partisan or polarising.

Nonetheless, an analysis of fact-checking reports published by Africa Check between February 2022 and October 2023 points to several common disinformation narratives that may be shaping online discourse about the war on the continent.

#1 Russia has Africa’s support and vice versa

Most of the fact-checked claims could be linked to one key disinformation narrative – that Russia enjoys the broad support of the African continent and vice versa. This narrative was largely perpetuated through social media posts and articles which highlighted the close relationship between Russia and African leaders or people. While it is true that Russia does have a close relationship with some African states, many claims exaggerated these ties or were outright incorrect.

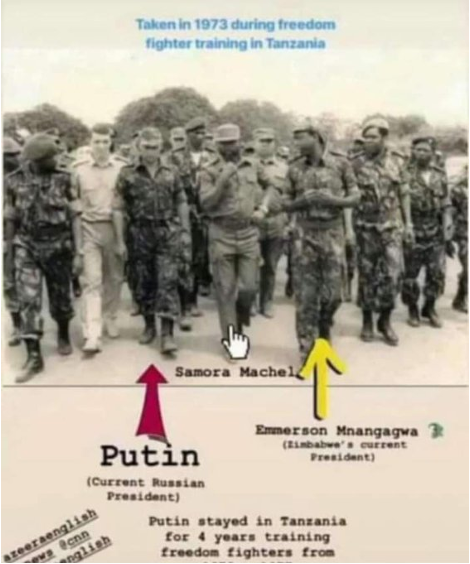

For example, shortly after Russia’s invasion, a grainy photo resurfaced claiming to show Russian president Vladimir Putin training African freedom fighters – including Mozambique’s Samora Machel and Zimbabwe’s Emmerson Mnangagwa – in 1973.

The photo had been circulating on websites and social media since at least 2018. Most recently, it has been used to argue that Africans should support Russia in the war because Putin had trained freedom fighters from South Africa, Mozambique and other neighbouring countries to “stand against Western bullies”.

While the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) did provide military aid to resistance movements in some African countries, experts said it was highly unlikely the man in the picture was Putin. It is also important to note that both Russia and Ukraine were part of the USSR.

Claims have also focused on Russia’s current support for African countries, particularly in West Africa where sentiment against France’s foreign policy has been growing.

For example, after the withdrawal of French troops from Mali in February 2022, images circulating on Facebook claimed to show Russian soldiers headed towards the West African country. The images were actually taken years earlier, in 2014. A video later claimed to show Putin at the 77th session of the UN General Assembly in September 2022, where he said Russia would “continue to provide all its support to the Malian people”. The video was filmed in 2015 and Putin was not present at the 77th session.

As calls for French forces to leave Niger grew, so too did claims of Russian support for the country.

In late July 2023, Niger’s elected government was toppled in a military coup. President Mohamed Bazoum and other political leaders were arrested, the country’s constitution suspended and state institutions shuttered. General Omar Tchiani declared himself the country’s new leader of a junta, or military government.

Hours after the coup, demonstrators took to the streets of Niamey, Niger’s capital, in celebration. Curiously, some waved Russian flags in scenes similar to those in Mali in May 2021 and Burkina Faso in October 2022.

In September 2023, a grainy video of a large plane descending over a dusty city began circulating on social media in Niger, Nigeria and South Africa, claiming to be a “leaked” clip of a Russian plane landing in Niger, carrying Wagner group mercenaries. While not officially linked to the Kremlin, Wagner is widely reported to be a proxy force of the Russian government. Since 2017, Wagner mercenaries have been active in several African countries, most notably Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic and Mali. Niger’s coup leaders did reportedly ask Wagner mercenaries to help them stay in power, but the video was 17 years old.

Also in September, images circulating in Senegal claimed to show military equipment delivered by Russia to Niger. None of the images could be linked to either country.

A much smaller number of claims were linked to an opposing narrative – that Africa was supporting Ukraine. For example, screenshots shared on Facebook in Namibia and South Africa claimed that Namibian president Hage Geingob said his country’s troops would “fly to Ukraine next week Monday”. This was seemingly to help Ukraine in the conflict.

The posts appeared to be from the official account of a daily newspaper, The Namibian.

The newspaper’s official Twitter handle is “@TheNamibian” but the account that made some of the false claims was “@Thenamibianewsl”. Using a handle or username that is similar – but not identical – to a trusted account is a common method used to spread disinformation in Africa.

A similar statement was allegedly made in March 2022 byNigeria’s then president Muhammadu Buhari. The image that circulated in the country appeared to be a screenshot of a tweet from the handle @MBuhari, Buhari’s official Twitter account.

The tweet read: “We stand with Ukraine at this trying time really after speaking to President Biden on his plans, I have informed my military personnel to be prepared for war! We will not let this slide.” However, it was fabricated.

#2 Russia is a global power to contend with

An equally popular disinformation narrative presents Russia as a global power. In this category, claims about Russia’s military power and global influence were common.

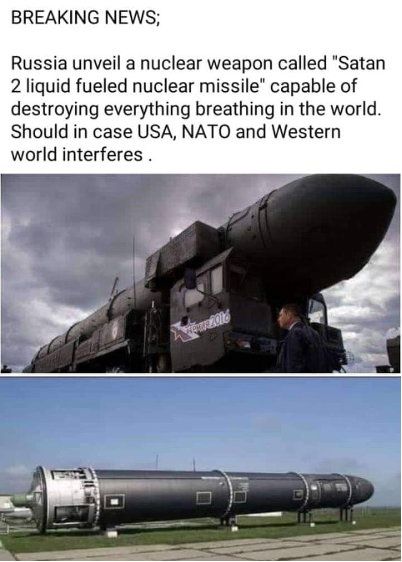

In South Africa, for example, claims circulated on Facebook and X in March 2022 that Russia had unveiled “a nuclear weapon called ‘Satan 2 liquid-fueled nuclear missile’ capable of destroying everything breathing in the world”. It would be used “in case USA, NATO and Western World interferes,” the posts added.

The claim began circulating online shortly after Putin said his country’s nuclear forces would be put on high alert. It was false.

Russia’s Satan 2 liquid-fuelled nuclear missile does exist, but it’s still in development and is not capable of “destroying everything breathing in the world”. And none of the photos showed the missile.

Other claims focused on threats or consequences of condemning Russia for its actions in Ukraine. For example, a video clip that circulated on Facebook and TikTok in Kenya claimed Russia was targeting African countries “with missiles for talking about Russian Ukrainian war”. The clip of Putin was real, but the subtitles were fake. In it, Putin announces a “special military operation” in Ukraine but makes no mention of plans to attack any African country.

Putin supposedly issued a similar warning to South Africa, with a statement warning the country to “desist from meddling their nose on the Russian affairs”. This claim appeared in the form of a graphic and appeared to show a social media post by South African news agency News24. It circulated on Facebook, X and 9GAG. But News24 said it had not published any such article.

Similarly, when the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (Fifa) announced that Russian teams would be suspended from participating in its competitions, a graphic quoting Putin as saying “Russia will play at the Qatar 2022 FIFA world cup or there will be no world cup to talk about,” circulated on Facebook in several African countries. There is no evidence Putin said this.

Also under this category are claims that Russia has weighed in on global issues by giving warnings to “rival” countries or organisations. For example, in October 2023, social media posts on sites such as Facebook, X, and the conspiracy theory-friendly video-sharing platform Rumble claimed that Putin had publicly threatened the founder and chair of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab.. However, the quote was completely fabricated.

Another video claims to show Putin issuing a stern warning to the United States, saying: “America should not interfere in #IsraelPalestineWar, if America does that we will openly help #Palestine”. The clip included a recording of Putin speaking in Russian, with English captions alleging Russia’s support for Palestine: “I am warning America. Russia will help Palestine and America can do nothing.” However, the captions were fabricated. Putin spoke in December 2022 about nuclear weapons in the Russia-Ukraine war.

#3: There is no war in Ukraine

During the first weeks of the Russian invasion, claims that the war was entirely fabricated began to circulate in South Africa.

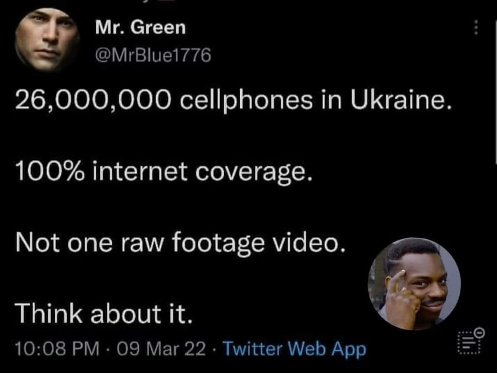

A typical version of one post read: “26,000,000 cellphones in Ukraine. 100% internet coverage. Not one raw footage video. Think about it.”

The allegation that there was no evidence of war was seemingly backed up by claims that US news channel CNN had misreported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that a 2015 photo showed an explosion in 2022.

Months later, in October 2022, Africa Check fact-checked another set of claims, circulating in South Africa that footage of the war in Ukraine had actually been filmed by US actor Sean Penn. As is often the case with disinformation, the claims exploited a kernel of truth. In November 2021, months before the invasion, Penn visited Ukraine to film a documentary. However, this is not evidence that Penn was preparing for a choreographed invasion. News reports written at the time of Penn’svisit make it clear that the documentary was meant to be about what was then only a “proxy war” between the two countries.

These claims were part of a series of vague conspiracy theories, also shared in Europe, that the Ukraine war is a “hoax”, “scripted and staged” to further the aims of Covid “plots” and a shadowy and sinister global elite.

Fact-checkers and news outlets were quick to debunk these claims. They also verified real phone footage of the invasion shot by people on the ground in Ukraine.

#4 Ukraine as the bad (and good) guys

Although less common, disinformation also focused on the role of Ukraine, with claims often portraying the country’s people, army and president in a heroic light.

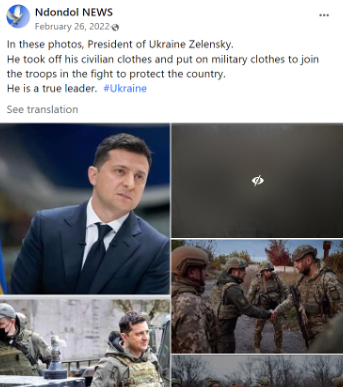

For example, in February 2022, days after the invasion, images of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy in military uniform began circulating online in Senegal. They were accompanied by claims that Zelenskyy had shed his civilian clothes and joined “troops fighting to protect the country”. All of the images were taken out of context, having been originally captured months before.

Similarly, images of a woman in military uniform and armed with a weapon circulated in Senegal and Zambia, claiming to show the wife of Ukraine’s vice president who “fights for her homeland”.

In South Africa, pictures of a young girl confronting a soldier made the rounds on Facebook. “An 8 year Ukrainian girl confronts a Russian soldier telling him to go back to his country. This is courageous. Brave Girl…” the caption typically read. One post was viewed more than 2.5 million times in 24 hours. The girl in the pictures was not Ukrainian, butPalestinian, and the soldier was Israeli.

An equal number of claims could be linked to an opposing narrative – that Ukrainians are bad people or have links to Nazism. In South Africa, for example, photos of Zelenskiy circulated on Facebook with the claim that the small cross motif that sometimes appeared on his trademark green T-shirt was in fact the Nazi Iron Cross. The photos of Zelenskiy were authentic but the cross on his T-shirt was not the Iron Cross. It was the symbol of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, which can also be found on the ministry’s website.

In Nigeria, a video circulating on Facebook claimed to show “old footage” of Ukrainian Nazis’ murdering “Chechnya Muslims in cold blood”. The video was related to the second Chechen war, but only because it is a clip from The Search (2014), a war drama written and directed by French filmmaker Michel Hazanavicius.

Later in 2022, a video circulated in South Africa claiming to show “Drunken Ukrainians’ arrested for defacing the Qatar World Cup mascot with ‘Nazi symbols’”. However, it was a mashup of unrelated images and appears to have been produced simply to support Russia’s accusation that Ukrainians are Nazis.

Posts like these reinforce Russia’s claim that the invasion of Ukraine was necessary to “denazify” its smaller western neighbour.

Conclusion

The investigation carried out by Africa Check, with the support of EDMO, clearly shows that disinformation about the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and more generally about Russia, is a relevant phenomenon in many African states.

To address and counter disinformation about regional and global issues, such as those mentioned above, it is fundamental to create partnerships across different geographical regions. This attempt led by EDMO shows encouraging results in terms of capacity building in different regions, increased awareness and relevance of the findings, and will hopefully be the first stone in a larger edifice.

The amount of topics characterised by significant disinformation phenomena, that could benefit from a cross-continental cooperation, is in fact potentially huge. Migration, foreign policy, climate change, economy, health-related crisis, just to mention a few examples, are all impacted by disinformation. To reduce disinformation’s harm, and in particular to counter its goal of widening the cracks in societies, greater cooperation between different actors spread in different regions of the world is of paramount importance.

Photo: Flickr, Dmitry Djouce