An analysis of the EDMO fact-checking network. Organizations that contributed to this analysis: PagellaPolitica/Facta, Polígrafo, The Journal – FactCheck

This article is the English translation of the original Unità di politica e mass media: così Portogallo e Irlanda hanno vinto la sfida dei vaccini, published on Pagella Politica the 26th of October 2021.

Last week, the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) fact-checking network published an analysis of the pandemic situation in Bulgaria and Romania. The two countries are the least vaccinated across the European Union — not because of a shortage of doses, but because of a lack of demand for vaccines by the population — and consequently feature the highest number of COVID-related deaths.

We investigated the reasons behind this situation. In addition to disinformation, other elements played a key role, including lack of trust in the political class and institutions, division and polarisation in society, poverty and low levels of education, and issues with the quality and independence of the information system.

Having looked at the two worst cases in the EU, we decided to focus on the two best cases of vaccination campaign success, Portugal and Ireland. Let’s first look at the data and then at the reasons for their success.

Data from Portugal and Ireland

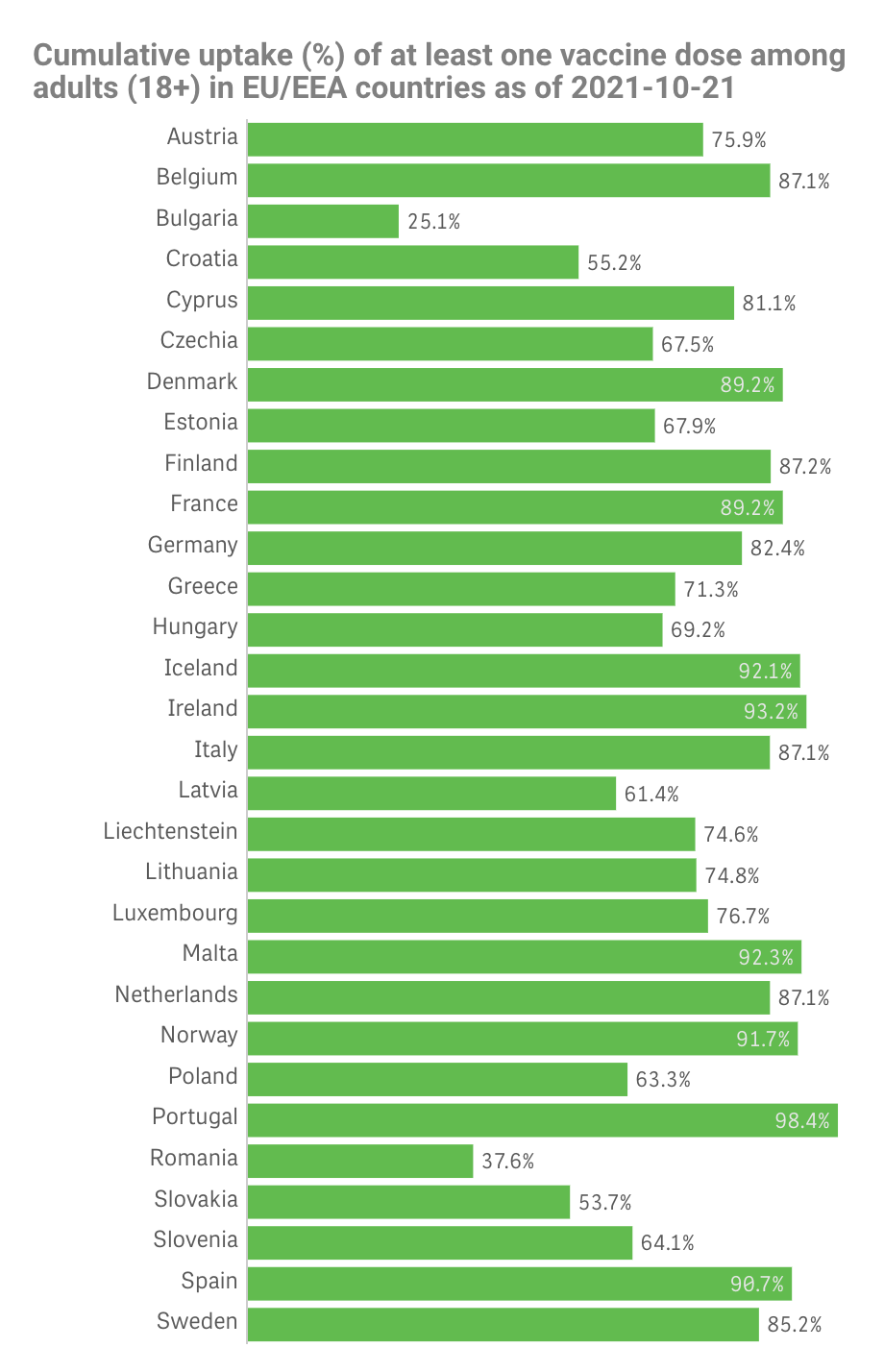

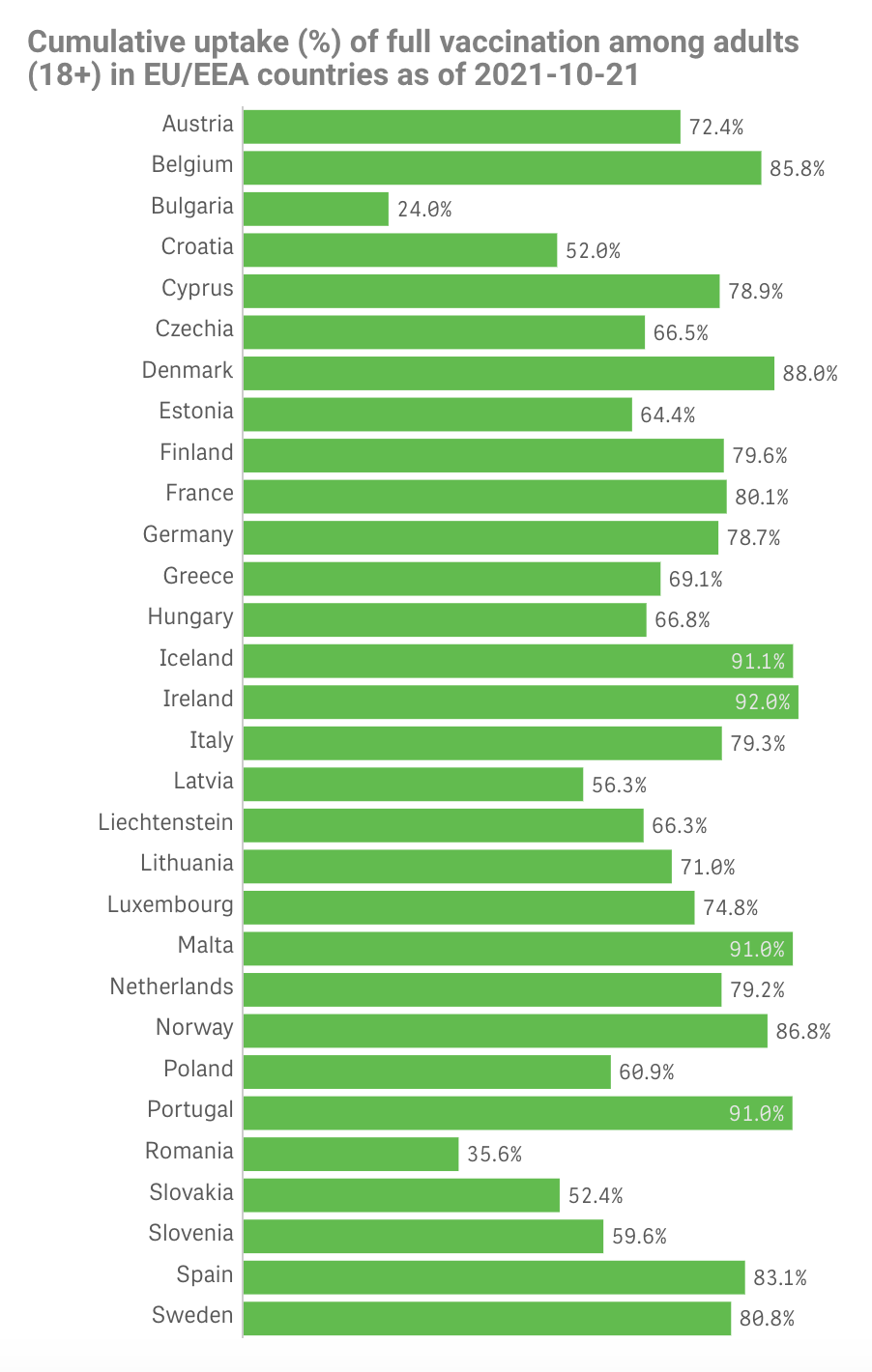

Portugal — according to data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), updated to 21 October 2021 — has the highest percentage of adult population vaccinated with at least one dose in the EU, 98.4%. The EU average is 79.7% (almost 20 percentage points lower). Ireland ranks second, with 93.2%.

Looking at the fully vaccinated population, the top positions are reversed. Ireland arrives first, with 92%, and Portugal is second, with 91% (the same as Malta). The EU average here is 74.4%.

Portugal

Fernando Esteves, Director of the Portuguese fact-checking organization Polígrafo, said that there are “two main reasons for the huge success: organisation and belief in the vaccination process”.

Regarding organisation, according to Esteves, the choice of Vice Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo to lead the vaccination campaign was a key factor. “He did a terrific job, by seeing the mission against Covid-19 as a war. The central approach has always been to plan and not to improvise, which is not very common in Portugal”. The logistics of the vaccination campaign seem then to have worked well.

Regarding the confidence of the population in the vaccination campaign, according to a September 2021 Eurobarometer survey, Portuguese have the highest proportion of population believing that benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh possible risks (87%, compared with an EU average of 71%) and the largest proportion of population considering the vaccine to be a civic duty (86%, compared with an EU average of 66%).

But how has this trust been built and how has the circulation of fake news not compromised it?

“There was a lot of circulation of misinformation about the lack of effectiveness of vaccines, especially on social media”, Esteves explains. “However, there was also a massive national mobilisation of traditional media, joined by the most influential opinion leaders, to defend the vaccination process”. Televisions have frequently hosted distinguished doctors and scientists, who have constantly highlighted the success and the importance of the vaccination campaign. Fact-checkers in Polígrafo also gave an important contribution, working together with health authorities and participating in popular TV broadcasts, focusing on the verification of disinformation on COVID-19.

But the credit should not just go to the media. The Portuguese political class has also shown great responsibility. “There was a rare national unanimity on the subject”, said Esteves. “Politicians did not use the vaccine issue in the political debate, promoting a broad national consensus”. As a result, there has never been a significant and formally organised anti-vaxxers movement in Portugal.

However, the small fringe of Portuguese conspiracy theorists has different characteristics in common with the most extremist fringe of the anti-vaxxers movements in other European countries. For example, the protests occasionally degenerated. “They have organised several public protests and have even tried to physically attack Gouveia e Melo, the leader of the mission unit. He was insulted and called a murderer by dozens of anti-vaccination protesters near a pavilion where 16 and 17-year-olds were being vaccinated”, says Esteves. The Vice Admiral has been under special protection since then. Journalists are another recurrent target of the no-vax, and Polígrafo’s fact-checkers have also been the subjects of smear campaigns.

In contrast to other countries, however, in Portugal, this particularly extremist minority has not been able to rely on the support of political forces or mainstream media. Therefore the anti-vaxxers never had the support of significant parts of the population that has become sceptical and scared of vaccines.

Ireland

Several elements that contributed to the success of the vaccination campaign in Portugal are also present in Ireland.

According to an interview held in late August with Professor Brian MacCraith, who chairs the Irish Task Force on COVID-19 vaccinations, Ireland’s success depends in particular on three elements: an educated population, the quality of information and a high level of trust in science and authorities’ indications. In this regard, it is worth noting that, even if it does not reach the Lisbon record, Dublin is high in the rank of EU countries for the percentage of population having confidence that the benefits of vaccines outweigh the risks: 80%, almost 10 points above the EU average. But where does this come from?

According to Christine Bohan, from The Journal — FactCheck, the Irish population has varying levels of trust in the political parties but “there are generally high levels of trust in the authorities and particularly in the public health system. Plus, we have good levels of media literacy here, I think – so while we did have some very vocal misinformation being shared, mainly on social media, most people seemed to recognise it as nonsense so it didn’t gain much traction.”

According to Bohan, disinformation is generally a fairly new phenomenon, given its size, in Ireland. After the pandemic started, “it was like misinformation just exploded overnight: suddenly there were large amounts of it, and for the first time we saw social media accounts sharing huge volumes of false information which was being shared by a receptive audience” she says. “What we’re seeing now is that misinformation is higher than it was before the pandemic — Bohan continues — but false news, and particularly misinformation about the Covid-19 vaccines, is speaking very much to an echo chamber. A vocal and very angry echo chamber, but it’s a really small percentage of people, and they’re not getting a lot of attention and most people don’t believe them”.

A similar use of a heated language appeared in Portugal as well, and this phenomenon is well spread in many other European countries. But the number of anti-vaxxers in Ireland is very small and, thanks also to the good information provided by the media and the authorities on vaccines, they have not been able to capture the attention of those who are out of their echo chamber. Moreover, in addition to providing good information, the mass media have also avoided spreading misinformation: they have never hosted the “VIPs” of disinformation with large followings on social media nor their positions. “Basically, if people want to get anti-vaxx info — said Bohan — they have to find the information for themselves on social media”.

Turning to the role of politics in the success of the vaccination campaign, Bohan stressed that in Ireland “all the political parties are pro-vaccine, on both the left and the right. There are one or two individual members of parliament who have spoken out against it, but no-one has paid much attention to them and their views have not been amplified much or had much effect”.

Bohan said also, in conclusion, that in Ireland “we haven’t had a growth in dodgy populist parties in the wake of the recession in the 2010s. So our politics and our media isn’t as adversarial as most other countries seem to be. We don’t have many public figures who deliberately spread misinformation, and we don’t have political movements which grow based on misinformation”.

One of the consequences of this less confrontational scenario is the absence of a strong no-vax movement in Ireland. In the recent past, the most crowded protests have been mainly against lockdowns and were motivated by their effects on the economy. On the contrary, there have been few protests against vaccines and with little involvement.

In conclusion

The cases of Ireland and Portugal seem to show, from the opposite perspective, what emerged from the analysis of the situation in Bulgaria and Romania: an educated and informed population that trusts the authorities, a political class united in supporting the vaccine, and a mass media system that provides correct information and does not give space to no-vax theses, are key factors in having a high percentage of people vaccinated.

Although disinformation exists in those countries, perhaps also reaching considerable volumes, it remains confined to the small spaces of the echo chambers of social media, without being able to reach and convince the general public. Not unlike the virus itself, if disinformation does not find healthy guests in politics and information to spread, contagion remains limited.

Tommaso Canetta, deputy director of Pagella Politica

*Fact-checking organizations that contributed to this analysis: PagellaPolitica/Facta, Polígrafo, The Journal – FactCheck

Photo: Pexels, Gustavo Fring